Businesses have three fundamental optimization paths:

Performance (Good). Products are crafted to be superior in quality, surpassing all competitors. This path prioritizes excellence over speed or cost, leading to expensive inputs, premium labor, and longer production times. Speed and expense become secondary concerns, sacrificed willingly to maintain unmatched quality.

Speed (Fast). Products are rapidly developed and swiftly brought to market. Businesses optimizing for speed capitalize on emerging opportunities, have the agility to pivot quickly, and prioritize rapid learning. Quality and cost take a backseat to the urgency of being first or fastest, either in response to change or by initiating disruption.

Expense (Cheap). Many large, incumbent corporations gravitate toward expense optimization, emphasizing efficiency above all else. Here, the goal is minimizing input costs—cheaper labor, lower-priced materials, and acceptable but mediocre quality—to maximize profit margins at scale, often without pursuing new markets.

An old adage summarizes these trade-offs clearly: “Fast, cheap, or good—pick two.” However, a more nuanced truth is that while you may strive for all three, you can genuinely optimize only one.

Symptoms of Expense Optimization

If your organization primarily pursues cost efficiency, several distinct features will surface:

Layoffs. Companies use layoffs to cut labor expenses and improve apparent efficiency by eliminating roles not directly contributing to profits. The aim is fewer inputs for the same output.

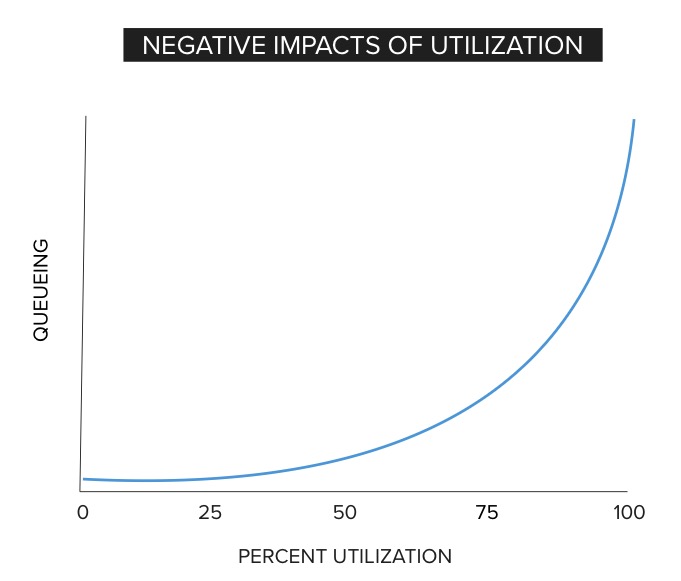

High Capacity Utilization. Efficiency-driven companies insist on maximizing employee productivity, pushing for near-total utilization. Management assumes more assigned tasks equate to greater output, sometimes artificially inflating workloads to protect staff from layoffs by appearing fully utilized.

Extensive Work Estimation. Organizations obsessed with efficiency invest heavily in detailed estimation processes to precisely allocate capacity. Effort is expended on creating, reviewing, and revising these estimates to align actual performance closely with projections, aiming to squeeze maximum productivity from limited resources.

Holding People Accountable. A pervasive mistrust arises from the belief that workers won’t voluntarily offer their full capacity. Consequently, management installs reporting and automation systems to monitor active work hours and idle time, sometimes using intrusive tracking software. Employees may face scrutiny or punishment if actual performance deviates from estimates.

Expensive Coordination Systems. With large work batches processed by numerous teams simultaneously, extensive coordination becomes mandatory. Companies appoint dedicated coordinators, project managers, and entire departments (PMOs) solely responsible for managing dependencies and maintaining workflow. This bureaucratic complexity, intended to boost efficiency, ironically adds substantial hidden costs.

Hidden Costs of Efficiency

While standard accounting (GAAP) clearly recognizes the savings from expense optimization, it rarely captures the hidden costs generated by these practices:

Declining Throughput. Utilization rates beyond 60-70% dramatically slow throughput, causing delays and reducing the organization’s agility.

Complexity Costs. Managing large batches increases complexity, dependencies, and thus slows production and responsiveness.

Coordination Overhead. Costs associated with the management layers required to coordinate complex workflows are rarely accounted for transparently.

Estimation Costs. Detailed estimation processes are expensive and often as inaccurate as they are extensive. As utilization rates climb, the accuracy of these estimates decreases sharply, further undermining productivity.

Hidden Expenses of Accountability

The drive to “hold people accountable” generates unrecognized costs, including:

- Purchasing and maintaining employee monitoring systems.

- Productivity losses from diminished morale.

- Time spent by management on enforcing accountability.

- Increased employee turnover and talent drain, leaving primarily employees unable to find alternative employment.

Ironically, such costs rarely appear on balance sheets or income statements, obscuring the true financial impact.

The Illusion of Efficiency Gains

When capacity utilization exceeds 60-70%, productivity and throughput diminish exponentially. Highly utilized systems may appear efficient superficially but become slower, more complex, and increasingly inefficient in practice.

Additionally, work estimation accuracy deteriorates as utilization rises, as no single team fully comprehends dependencies and bottlenecks across the organization. Attempting precise estimates under these conditions often yields misleadingly optimistic projections.

Opportunity Costs and Misaligned Incentives

Layoffs might temporarily boost stock prices by signaling decisive management action. Still, the actual business benefits are minimal, short-lived, and overshadowed by the long-term systemic damage: decreased throughput, lowered product quality, heightened employee stress, and reduced innovation.

Accountability culture further compounds this misalignment, increasing operational overhead while diminishing productivity and organizational health. The superficial productivity gains from “holding people accountable” rarely offset the hidden but significant costs.

As queues grow, production slows stretching expenses out over more time. As quality drops, more defects are worked, further consuming capacity expense, increasing queues further, slowing production even more and furthering those expenses. In essence, optimizing for expense and pursuing efficiency merely redistribute expenses while appearing to reduce them.

The Bottom Line

Ultimately, optimizing for expense through excessive efficiency often fails to deliver genuine, sustained business value. Short-term financial gains typically obscure deeper, systemic issues that reduce overall productivity, innovation, and agility.

When considering “Fast, Cheap, or Good,” organizations must recognize that true efficiency involves trade-offs—and excessive optimization in one dimension inevitably leads to hidden costs elsewhere.

Long-term success requires acknowledging these trade-offs openly and making strategic, transparent choices rather than succumbing to short-term illusions of efficiency.

- Reinertsen, D. G. (2009). The principles of product development flow: Second generation lean product development. Celeritas Publishing. ↩︎