The words measure and metric are used interchangeably in business, however, they are not the same thing. A measure is a quantification, while a metric is description of a measure. This is not mere semantics. Knowing the difference is helpful, because you need both measures and metrics to determine the value of an outcome. Without knowing the difference, you will deprive yourself of one or the other.

Measures

Measures are easy. A measure is a quantification. These are all measures:

- We built 12 features this sprint

- There are 6 projects in the pipeline

- My boat is 21 feet long

- My car gets 25 miles per gallon

Any time we take any sort of ruler and compare our results to the ruler and get a quantification, we have a measure. Measuring is powerful, if you measure the right things.

Most people in business do not measure the right things. But that is a topic for another article.

Metrics

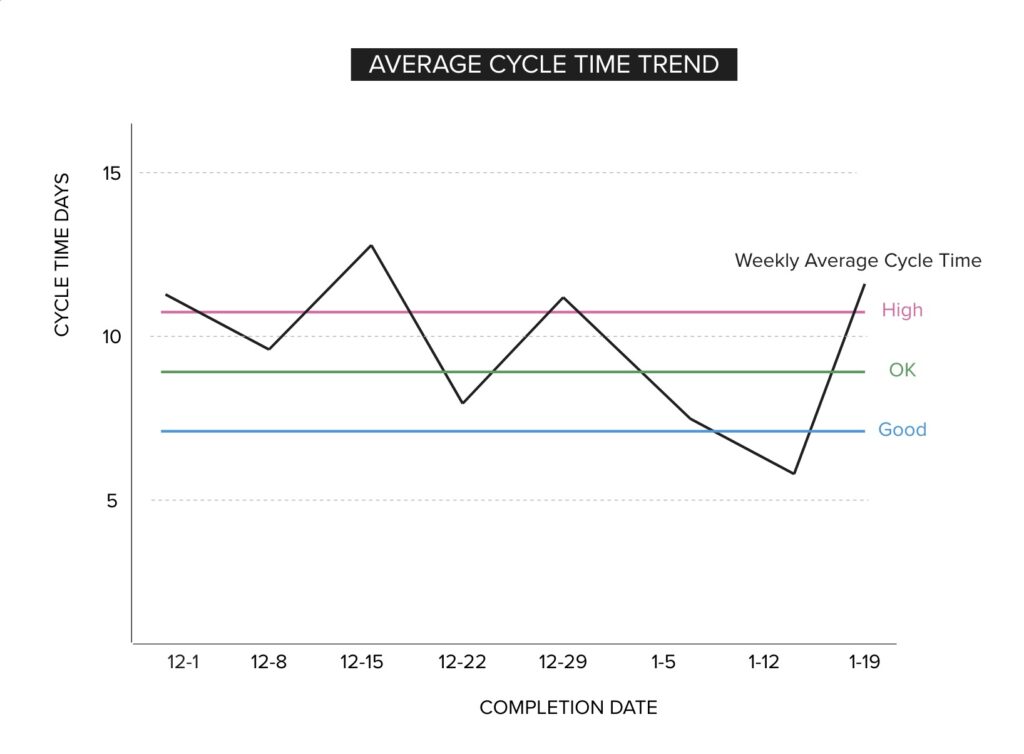

Metrics are descriptions which help interpret what the measures mean. Take a look at this example of a cycle time chart. The average cycle time recorded for each week is the measure (black line). The high, OK, and good markers on the chart are metrics. They tell us what the measure means.

This chart is a fictional example I threw together quickly. You should not infer from it that a cycle time of 9 days is OK. For many teams, a cycle time of 9 days is a disaster.

The Value of Metrics

Mixing up the words metric and measure cause us to lose the meaning of measures. Think about the things you measure. Why do you measure them?

An example from my experience is counting projects delivered. What is the value of knowing the number of projects delivered? That measure is useful if the only thing you are interested in doing is impressing someone with your ability to count projects. Perhaps there are many projects completed, and you wish to impress with the large number to create the impression that a lot of work is getting done.

I wouldn’t want to run my business based off of a feel-good measure like “We did a lot of projects. Here’s the number.” What is a good number of projects? What number is not enough? What number is the sweet spot? What number is too many projects to have reasonably worked on? Without an accompanying metric, I don’t think the measure tells us anything.

This leads us to another interesting thought: if there is no metric that tells us where the measure should land to indicate value or success, such as number of projects completed, then perhaps you are measuring the wrong thing! In this case, there is no good metric for the number of projects completed, because completing projects does not directly tie to business success.

Every single project completed could have been a waste of time. Perhaps few or none of them were of any value to the business. Our failed attempt find a metric for the measure of completed projects that describes the meaning of the measure reveals the measure has no meaning. The number of projects completed is not a useful measure.

Vanity Measures

A vanity measure is any measure that an organization publishes which creates a number that has no meaning to the business. Examples of vanity measures I have seen include:

- Number of projects completed

- Number of people currently employed

- Total revenue so far this year

- Number of sales

- Number of new features deployed

- Number of tickets resolved

None of these measures can have a metric that describes them. They are vanity measures. These measures exist to create counts of things which look impressive to the untrained eye. But they are not valuable measures. All of these numbers can be lower or higher, and no success or failure is indicated.

Valuable Measures

A valuable measure will have a metric associated with it. It will indicate a desired outcome is achieved or not. In other words, the measure can be compared to a goal and we will know if we were successful or not. The value of a measure is dependent on the context of the organization doing the measuring and what their goals where.

Here are some valuable measures that large businesses might use for which there are accompanying metrics:

- Revenue per employee. The organization had a revenue number per employee when they started measuring, and they asked the leadership team of every team to raise this number and not allow it to go down. This put a stop to adding additional workers every time there was an ask for new work, and instead refocused the organization on improving their process, working on fewer things, and building fewer, more valuable things.

- Profit. Measuring profit is useful. Many organizations measure EBITDA (earnings before income taxes, depreciation, and amortization). Profit tells us if the business is, at least in the short-term, making more or less money than it was. Making profit is nice, but an upward trend is preferred. Many businesses also concern themselves with an increasing margin of profit from revenue.

- Average revenue per user. ARPU I have seen used previously to indicate that each customer is valuable. Servicing many customers for tiny amounts of revenue indicates a business is doing too much work and running with too much overhead to please too many customers. It is an inefficient operating model for ARPU to be low. The higher it is, the more each customer spends, the more valuable all customers are.

Here are some valuable measures that a product development team should consider instead of the vanity measures of velocity and features delivered:

- Team goal is to reduce defects and improve quality so they measure the number of defects per sprint, the change failure rate, the number of defects per feature (if things are really bad), or the number of problems found during a testing cycle further upstream. The metric here is zero is great, fewer are better, and higher is bad.

- If the goal is to deliver the right things and please the customer, then the team can measure customer and stakeholder satisfaction. The trick to measuring something like this is to do it frequently with an extremely light touch. No one wants to take a 15 minute long survey. But a quick show of hands or a single question tossed into a conversation can be extremely powerful. A metric is clearly available: higher satisfaction is better, lower is bad. NPS (net promoter scoring) uses this method.

- If the goal is to speed delivery, the process can be mapped, work tracked as it flows through the system, and a series of measures or a single large measure can be collected as a cycle time. The metric: faster is better. The work: make a change to lower cycle time. If it doesn’t go down, discuss and try something else.

Summary

A measure is a quantification, but without a metric has little value. Metrics describe measures. When we compare a measure we take against a metric, we learn what the measure is telling us. Our inability to find a metric for our measure possibly means that the measure itself is without value. Valuable measures are those where we set a goal, and then we measure our progress toward that goal.