When a group of people start a new business, they work in a powerful, agile team. They probably don’t even know that they are structured in an agile way. But they are. What makes a start up so powerful, and how can a larger organization or a division of a large organization operate more like a startup to reap the benefits?

When first starting your own business, unless you have powerful financial backing, you are probably doing all of the work yourself. You are the board of directors, the entire C-suite, the factory, the advertising, and everything. You operate alone in a highly effective manner.

Up to a point.

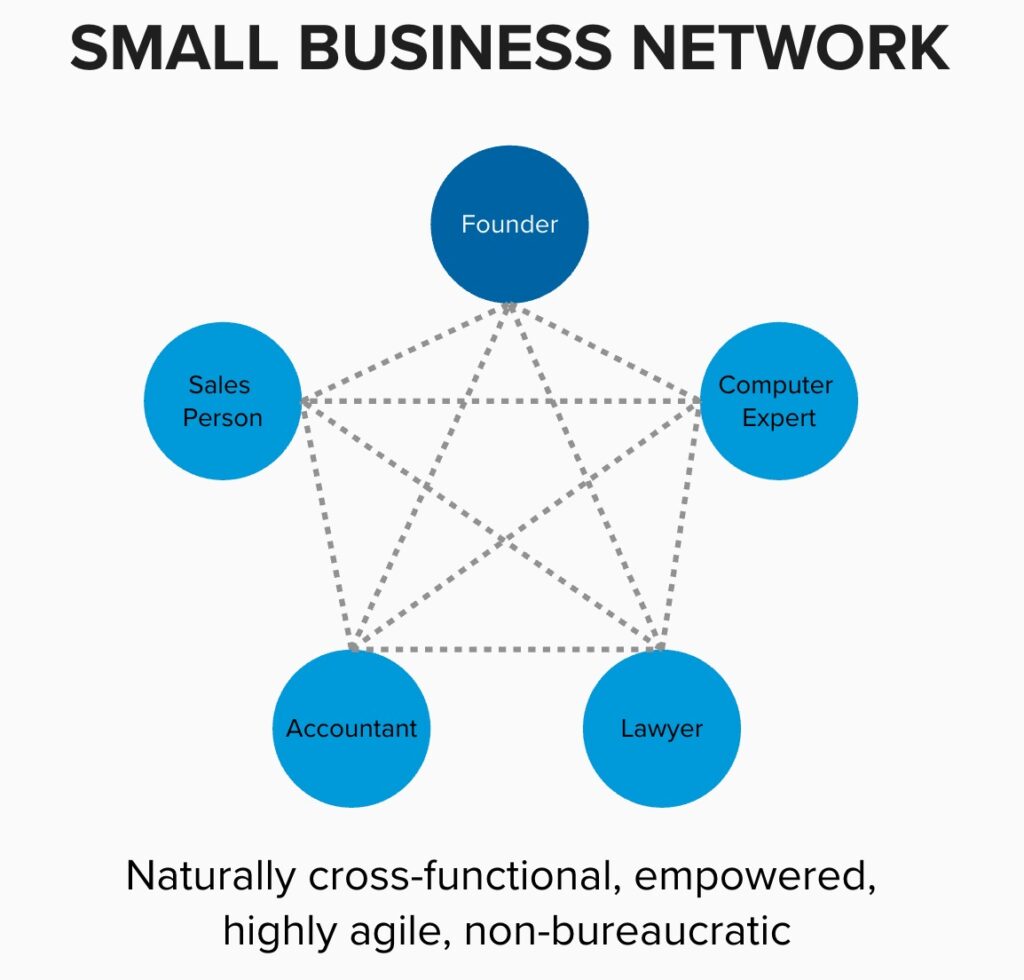

Then you finally hit a wall and realize that you have a problem you cannot solve yourself. You might need an extra sales person to man the storefront or go meet with customers. You enlist the services of an accountant to help you with complex tax code questions and filing. You will eventually end up with a lawyer because someone will sue you. At that point, you now have started to build your cross-functional team.

The Network

Your startup team is highly networked. Most of the people know and talk to most of the others on a regular basis. There is no staff meeting. You all simply communicate as needed and arrange to work together when required. There is no formal communication, as usually text messages and phone calls suffice when not in person together. The culture is informal, fast, and focused entirely on developing the product or service and adapting to what you learn as you go. Slowly, the business builds.

This initial team is an agile team, even if you did not intend it to be one.

- Small. Your team is not large. You have a person for each essential function that you lack the expertise to perform. A small group of people can make decisions rapidly and communicate with one another effectively.

- Cross-functional. Your team has all the skills needed to perform the work. Each person brings something the others do not have. You may have some other employees who serve more as “hands” to do work such as manning a store front on weekends, but the team is composed of people who work together sharing their individual expertise with one another as a team.

- It’s a real team. Your team shared an outcome. They all want the same thing: success for this business. As the startup group, they have a vision for what success looks like that is very clear to everyone, and they also have personal visions for how they will be successful when the business succeeds.

- Self-managing. A startup owner is not barking orders at their lawyer and accountant. They are partnering with them, knowing that they need their expertise to survive. The team members are not assigned work, but rather advise one another and perform their work as needed on-demand.

This team is nimble, fast-moving, making decisions on the fly, communicating frequently, and working through their problems one at a time.

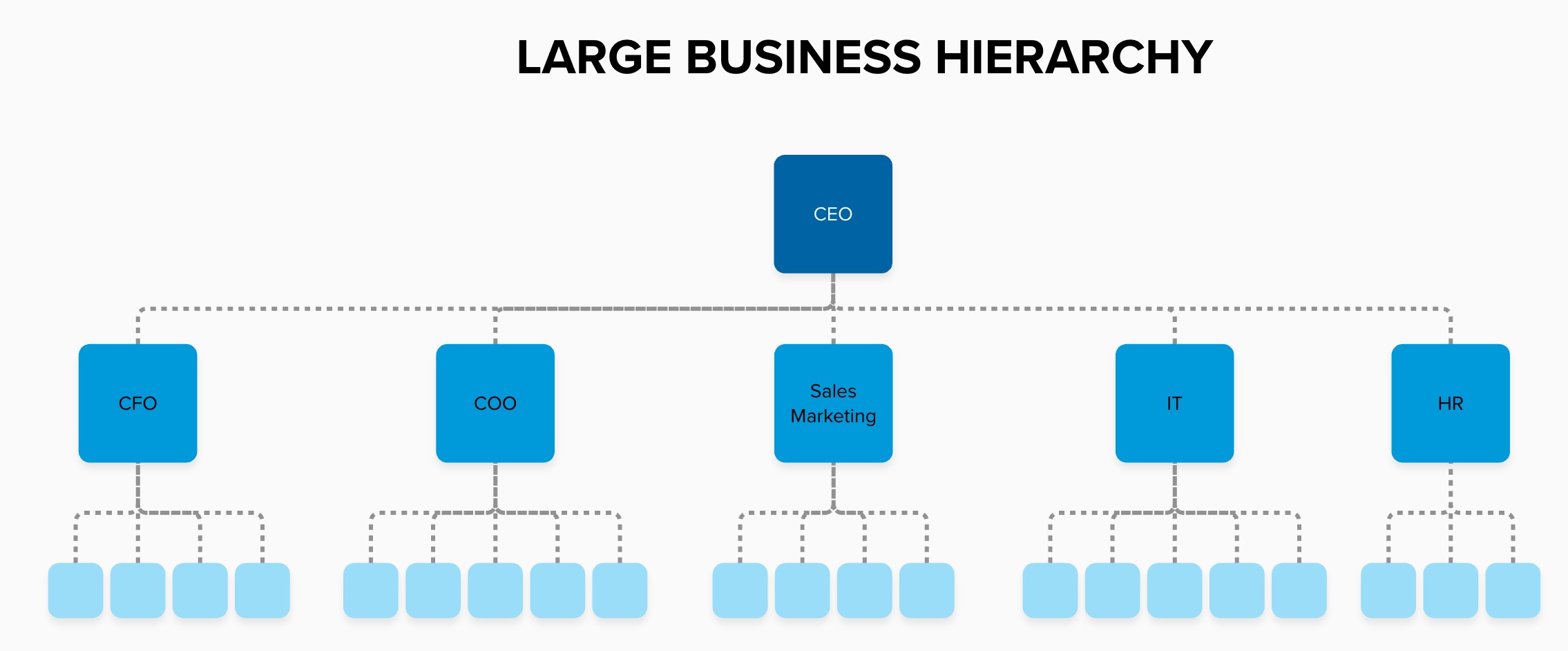

Growth Leads to Hierarchy

As the business grows, the original crew require more hands to help them do their work. Naturally, as the original group in charge, they do not move to create more teams like their own and empower them over different areas of the business. Rather, they expand their own personal capacity in each case. The IT team expands under the IT expert. The sales team grows under the lead sales rep.

The network breaks and now communication starts to become top down. Rather than having a circle of people tightly networked together, the business is organized for vertical communication. Functional silos allow each specialty to assign work and find where it went. Top-down decision-making is enabled as is accountability to control spending through resource utilization.

Formality of communication goes from a phone call filled with F-bombs and laughter to formal emails with official notifications placed under the company’s logo with official signatures. Decisions and spending are reviewed. Budgets are prepared. Projects are numbered. More experts join the company from other medium and large businesses, and they bring with them what they learned in their previous jobs: governance and control.

This chaos needs reporting, standardization, and centralization.

Hierarchy Pitfalls

The hierarchy has created a brittle organization that is no longer agile.

- Delays. The necessity of forming project teams across the organizational silos to perform work slows down work and creates overhead coordinating efforts.

- Formality. Completing tickets and calling 800 numbers to receive help creates queues which induce more delays into the system.

- Centralization. Strongly centralized functions often become bottlenecks. They also cause the organization to become globally vulnerable to injury. When things are heavily centralized, then any outage or problem becomes universal.

- Disengagement. People working in a functional silo often look down at their desks rather than outward at the rest of the organization. Do the people in sales understand IT? Does IT understand sales? Have they ever even met one another? Do some of them even know the others exist?

- Vertical Communication. Asking for permission for changes or improvements travels upstairs and decisions travel back downstairs. Most ideas and solutions are conceived upstairs and people downstairs are informed. People are not bought into these decisions and rarely feel enthusiastic about executing them. Decision-making is slowed as the approval queue is a bottleneck for change.

- Social distancing. The top level decision makers may work on a top floor or be physically remote from people doing the work, losing touch with complaints and issues that are faced day to day, resulting in decisions that are detached from reality.

- Overhead. As the organization silos itself into functional groups, coordinators must be hired to help ensure that all of the work can be tracked down and followed or found.

The hierarchy happened because the founding agile team preferred to retain decision making to themselves rather than delegating it to the new hires. Instead of explaining, demonstrating, guiding, and empowering, they hired people who were little more than extra hands for themselves. You can hear this in the language of hierarchical companies.

“You represent me in that meeting.”

“You speak for me.”

“You made me look bad.”

These sorts of expressions reveal that the person at the top views the people who work for them not as empowered decisions makers. They see them as extensions of themselves. Who wants to be an extension of someone else?

Returning to Network

Organizing work and people so that rather than hierarchy the network is the model that prevails is not easy, but it is possible. It is also not a black and white decision that must be made in a flash cut. Instead of organizing by function, try instead organizing by product or service. Include in each team all of the people needed to do the work that the team will need to do so that temporary formation of project teams is minimized. Keep fixed capacity standing teams that work on products and services instead.

Empower these teams to make decisions about how they work. Retain only the most dangers decisions upstairs. Give people rules and goals, and then let them decide how to solve their own problems and make decisions for themselves. Give them the experience of the startup that was so successful.

Small, self-managing, cross-functional teams not to handle functions, but services and products. You won’t put a lawyer or an HR specialist on every team. That would be silly. Some functions will retain their shared nature and remain in silos because they are infrequently needed by most other workers. For people who need each other day to day, put them into real teams, give them a shared outcome, a vision of the future, a strategy you want to follow to achieve it, some rules and guard rails, a budget, and the authority to figure out how to solve the problem.

The fragile hierarchy with its delays, formality, and overhead costs can be diminished with effort.